The Mexican-American from Los Angeles holds the distinction of being the first Latino to represent U.S.A. in Olympic competition

You won’t find Joe Salas’ name among the inductees of the International Boxing Hall of Fame, and he won’t come up in discussions of the greatest boxers of all time.

Salas does, however, occupy an important place in the history books as the first Latino to compete on a U.S. Olympic team as one of the representatives who went to Paris in 1924. His accomplishment in not only competing but also winning a silver medal is remembered as part of National Hispanic Heritage Month, which runs Sept. 15 through Oct. 15.

First row (left to right) Fidel La Barba, Jackie Fields, Coach Spike Webb, Ray Fee, and Joe Salas

Top Row (left to right) George Mullholland, Adolph Lefkowitch, and Adolph Allegrini

“We hold Mr. Salas in the high honor as he was the first Latino in Olympic competition,” USA Boxing executive director Mike Martino said. “His courage to break the barrier was an extraordinary feat, and his influence has transcended the years as Latinos make up a majority of athletes that now compete for USA Boxing.”

According to USA Boxing, there are now 11,020 Latino athletes and 3,576 non-athletes including coaches, officials and others out of the total membership of 42,125. Latinos are the largest ethnic segment of USA Boxing’s membership.

A Univision Data report found that at least 20 athletes from all sports of Latino or Hispanic descent competed for the United States in Rio this year, of whom nine won medals, but it all started with Salas.

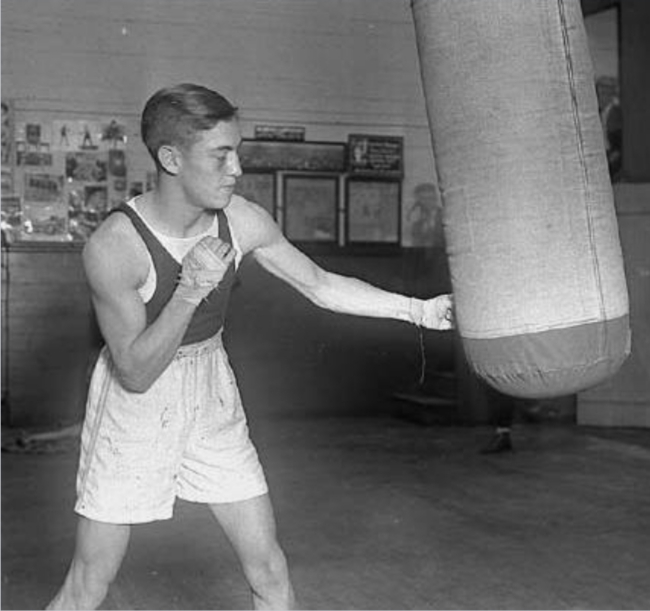

Born Dec. 28, 1905, Salas was one of the youngest of 11 children who grew up on the edge of Elysian Park in Los Angeles, a predominantly low-income neighborhood. It was there that Salas learned to box. When a professional boxer, Joe Rivers, moved into the neighborhood and set up a gym in his backyard, Salas took notice. He and his friends used to go and watch Rivers train, and after Salas got to be friends with Rivers’ son, he began to practice on the bags.

At just 14, Salas joined the Los Angeles Athletic Club. They had good training facilities, he said in a 1987 interview with the LA84 Foundation, and anyone could come in, so he went with a friend and joined.

Salas began training with George Blake, and the two worked together for two and a half years, sparring and doing all the things boxers do to train, Salas said. The gym was a hotbed of future Olympic boxers, too. Salas, Jackie Fields, Adolph Allegrini and Fidel La Barba were all from the neighborhood and trained at the gym before representing Team USA at the Olympic Games.

In 1924, Salas won the national AAU featherweight championship, which also served as the Olympic Trials, to earn his trip to compete in the Games of the VIII Olympiad, and was undefeated until he got to the Olympic final.

The boxing competition was five days, each day a different fight, but the final came down to Salas versus Fields, with whom he’d trained and grown up in their Los Angeles neighborhood.

“We were buddies,” Salas said of Fields in the LA84 interview. “We both started boxing together at the same time. We were born and raised within a couple of miles. We both broke into tears before the fight. But when you got in the ring, you had to take care of yourself. That was a way of life then. I remember the other boxers were trading tips at the Olympics. Everyone was friendly.”

The fight lasted three rounds with an extra minute in the third round before officials awarded the gold to Fields. The United States won the team competition with two gold medals, two silvers and two bronzes.

“The fight was so even that they couldn’t make a decision,” Salas said. “But he got the gold; I got the silver. It was just a matter of decision made by very fine Olympic officials. We knew that and whatever happened, we agreed. There were no hard feelings. I gave it my best and, evidently, it wasn’t good enough.”

Coach Spike Webb said in his official report following the Games that both boxers “gave a remarkable exhibition of scientific boxing and clean, hard hitting, and for the three rounds they put up a battle which will go down in the annals of history as being one of the smartest and cleanest battles ever fought in Europe. The decision of the judges went to Fields and it met with the approval of the crowd, as Fields boxed like a master, while Salas also gave a wonderful account of himself.”

After the decision, Webb wrote, Fields apologized to his friend then went to the dressing room and cried, but Salas “like a game battler that he is, took the decision without a whimper and no one was more sincere in congratulating Jackie Fields than Joe Salas.”

After the Games, Salas turned pro and went 42-6 over the course of his career. He also worked as a training assistant for the U.S. boxing team in 1932.

He died at the age of 83 on June 11, 1987, just eight days after Fields.

Karen Price is a reporter from Pittsburgh who has covered Olympic sports for various publications. She is a freelance contributor to TeamUSA.org on behalf of Red Line Editorial, Inc.